September 4, 2025

Demand from consumers for new and exotic cannabis genetics is ever present on retail and cultivation facilities. While fruity, sweet aromas may be in demand at one point in time, pressure for gassy more pungent aromas may soon follow. A robust genetic library from which cultivators may select is vital for the bottom line. Consideration must also be given to continually searching for high yielding and/or high testing genetics as pressure from shareholders in a highly competitive market continues to mount. Highly trained and experienced cannabis breeders are becoming highly sought after. This review briefly highlights some of the challenges associated with traditional breeding approaches as well as what the future may hold.

Traditional Breeding

It has been well established that cannabis has a tremendous amount of genetic diversity. This has led to the development of highly diverse strains. Also, being that cannabis is predominantly dioicous plant (male and females flowers on separate plants), traditional male/female breeding was widely used to produce new strains. This however leads to obvious issues such as having to sperate out male plants from females prior to flowering to avoid unwanted, widespread seed set.

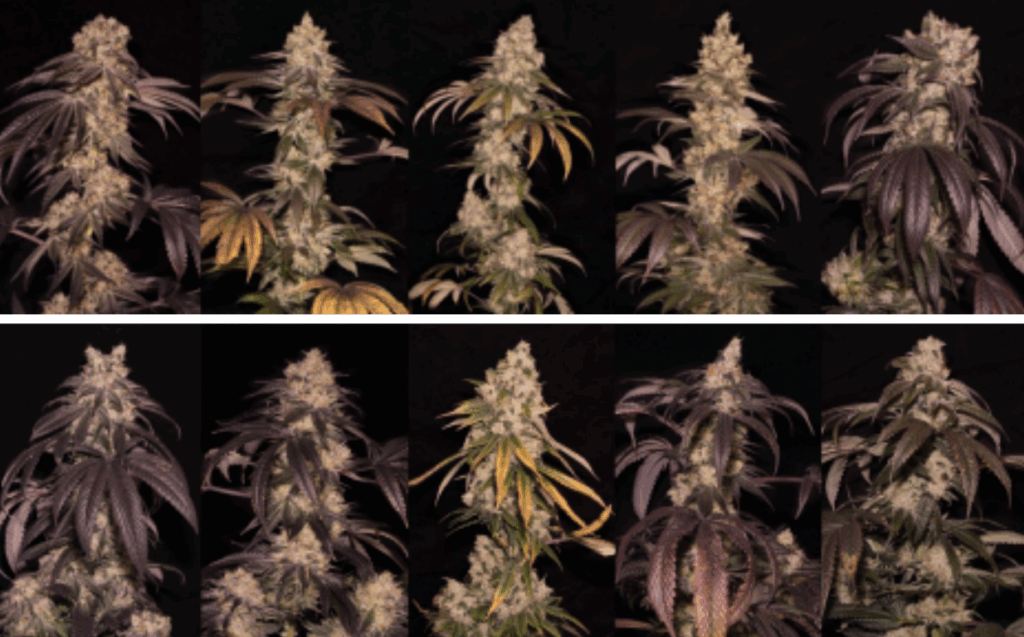

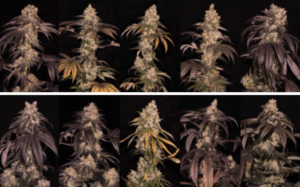

More recently, compounds such as silver thiosulfate have been used to chemically induce female plants to produce pollen which can then be used to produce “feminized” seeds. Silver thiosulfate, however, is highly toxic to both humans and aquatic life. Safer alternatives are available and can also be used to produce “female” pollen (Figure 1). One of the main benefits of using female pollen is that trait selection may be more predictable. For example, using well established, stable genetics that have been previously selected based on a specific agronomic train (yield, terpene content, bud structure, etc.) can lead to a high probability of finding those same traits in the first population of seeds or F1 population (Figure 2).

Figure 1: (Personal Picture) Pollen collected from “White Widow” in an indoor cannabis grow facility. Female White Widow plants were chemically induced to produce pollen using a safer alternative to silver thiosulfate. This pollen can then be used immediately on another female plant or stored for later use.

Figure 2: (Personal Picture) F1 hybrid phenotypes from a “White Widow x Bio Jesus” cross during the first stage of flower selection. These parental lines were selected to be crossed based on similar yield and cannabinoid content.

One of the main drawbacks of traditional breeding approaches can be the time it takes to go from germinating an F1 seed for example, to the first round of yield data and test results (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hypothetical timeline for pheno-hunting through a set of F1 seeds starting from germination through the end of flower.

While the search for commercially successful strains can take time, the process can help determine many important factors. Such as, does this plant work well with my “Mother-clone” system? Does a particular phenotype work well with my plant media and nutrient program? Taking time to assess a selection even early on in the vegetative phase for factors such as these prior to induction of flower can help companies make an informed, educated selection.

Future Breeding Technologies

In some way the future of breeding is already here. Using approaches like Marker-assisted breeding can speed up the time it takes to make a final selection. One of the most well-established markers for cannabis to date is the “Sex” marker. Commercial companies utilize this marker to help growers determine if a plant is male or female at a very early stage. Other markers that are starting to become more established are markers for “chemotype”. An example of these types of markers would be based on the genes responsible for producing THC, tetrahydrocannabinol acid synthase (THCAS). However, due to the tremendous amount of genetic diversity within cannabis, it can make finding these markers extremely difficult. In some cases, there are families of genes that can be responsible for the same function. For example, there may be as many as 25 different THCA synthase genes within the cannabis genome and determining which one of those is truly functional and responsible for the production of THC can take time.

Newer, more advanced breeding technologies such as gene editing may soon be utilized for cannabis as well. These approaches have been well established for other major agriculture crops. These approaches include technologies such as CRISPR. This approach allows for very targeted genomic modifications without any unwanted mutations. All of these more advanced breeding technologies require, among other things, a deep understanding of the genome itself. Currently for cannabis there is indeed an available genomic sequence. It is however not as complete as one would hope to fully utilize these technologies. Also, to perform these more advanced breeding approaches, cultivation facilities would have to invest a tremendous amount of money into setting up a lab with the appropriate equipment and labor.

Conclusions

Historically, obtaining new genetic material online was one of the main sources of new genetics. While current seed/clone sources online have improved dramatically, there is still much room for improvement. Strains offered as “Feminized” may in fact contain and handful of male plants that need to be culled from the facility immediately upon detection by an experienced grow team. This can be avoided by performing the breeding in-house to ensure the highest quality. Also, Certificate of Analysis (COA) should be provided from reputable genetic providers for either the specific selection being provided, or the parental lines used to create a particular batch of seeds. Nowadays with the threat of virus always looming, “virus-free” certificates will also become the norm when it comes to sourcing new genetics.

In-house breeding projects with established genetics may be the most economically viable approach at this time for the introduction of new strains. Either inducing females on site to produce pollen or utilizing previously stored pollen, both approaches can lead to a high probability of success. While breeders continue to search for the best of both words in terms of yield and THC, efforts should also be made to breed with aromas and consumer effects in mind. The continuous production of reliable/clean genetics will remain the one of the highest priorities for cultivation facilities.